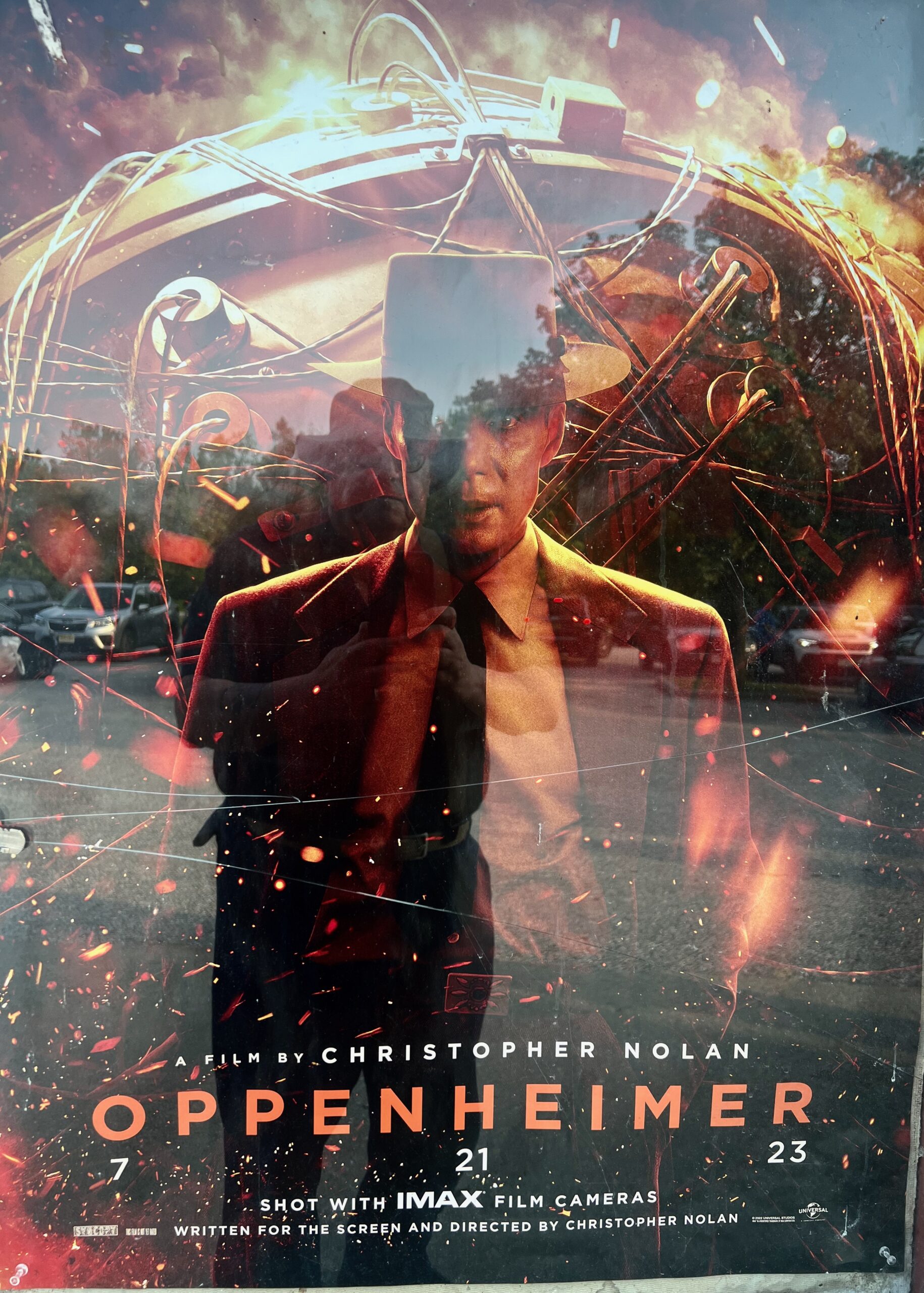

“Oppenheimer” is a profoundly important movie worth seeing (I’m going again Sunday). The word masterpiece comes to mind.

It is also a difficult movie in many ways, almost too complicated, up and down, back and forth, all over the place, for me to describe in detail.

I have to say it’s a cultural hoot to write about Barbie and Oppenheimer in the same week.

They are the literal opposites of one another; they offer great hope for the future of movies. There is nothing quite like them to make a point.

Oppenheimer tells the very turbulent story of Robert Oppenheimer (played wonderfully by Cillian Murphy), the American theoretical scientist who led the urgent and often panicked effort to win the global race to develop the two atomic bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II. This was a global cataclysm that triggered a new age for humanity and the earth.

Could the stakes be any higher?

Robert Oppenheimer was racing against the clock every second of the war and through the movie from his secret base at Los Alamos, New Mexico. He was chasing the Nazis and the Russians, and Germany was way ahead at the outset.

Oppenheimer gathered the best scientific minds worldwide, including the Jewish- German physicists who fled Hitler.

Had Hitler left his scientists alone, there is little question he would have gotten to the bomb first. This was a thought that made the made the movie even more haunting.

This dilemma was to cause Oppenheimer, a left-leaning Jew, trouble for the rest of his life. It’s an American thing – hero one day, goat the next.

His work and team ran headlong into entrenched anti-foreigners, suspicion, and Communist

hysteria in the military and Washington. Oppenheimer was a brilliant scientist but an impulsive human with poor judgment, a tendency towards sexual adventuring and unfaithfulness, and a streak of nearly fatal arrogance mixed up with idealism and terrible fear.

This is not the portrait of a simple man.

At times he was fearless; at other times, he was tragically weak. He could be as bright as anyone and naive and dumb as a child.

He was blunt and honest; he was weak and dishonest. He was also the man of the moment, the only scientist in the world who could, decided the Army, get to the bomb before Hitler.

Murphy the actor, does a remarkable job of capturing the life of this tormented and complicated person who changed the world’s history.

Oppenheimer covers a lot of ground, from the 1920s into the 1950s and a little beyond. It’s much to cover in a film and follow in a theater seat. I will see it again because much of it has sailed over my head. Christopher Nolan’s movies move fast. I missed some of the details.

But there’s no doubt about one thing: This movie by Nolan (Dark Night, Dunkirk) is terrific and powerful, and I would recommend that any thinking or curious person would go to see it. It’s about something that affects all of us.

In a sense, the movie collides head-on with our avoidance of the most critical issue facing the world right now, along with climate change: we all live under a terrible shadow.The prospect that a nuclear conflict could destroy human life on Earth hovers over the world.

Avoiding reality is the American way of dealing with nuclear war and climate change; most humans don’t want to think about it.

This may be why the movie touched such a deep nerve in the American psyche.

Surprisingly, this movie is a smash, a remarkable and hopeful thing. It’s nothing like Barbie, the other current hit, for sure.

Maybe we underestimate people. The film is a runaway blockbuster, earning 209 million dollars worldwide in its first weekend.

Note: My review philosophy (I was a media critic for a while) does not bombard readers with inside baseball movie talk or long-winded and largely irrelevant analysis. My idea is to tell overwhelmed and bombarded people drowning in information if the movie is worth seeing. I’ll try.

Without any qualification, the answer is yes.

I will say it’s too long – 3 hours – and while the first two hours are almost hypnotically gripping, the last hour seems to lose altitude and wander too deeply into the politics of 1954. That got me nearly bored, quite a contrast from the overall film, which had my eyes wide open and my hands gripping the armchairs.

I saw the movie in a small Vermont theater that is reliably empty. This movie was sold out at 4 p.m. Something big is happening here.

The movie skillfully captures much of the riveting process of producing the bomb. That’s a nail-biter.

From the beginning, the idealist scientists were caught in an impossible moral dilemma – Oppenheimer chief among them – between being successful and beating the Nazis and the havoc and danger they knew they were about to unleash on the world.

They were idealists; they believed science should better people’s lives, not slaughter them. That agony was woven into the movie.

There is no good place to land in that agonizing choice; the movie captures that brilliantly. Nolan chose not to show any images of the devastation the bombs caused in Hiroshima and Navasake. Oppenheimer frequently imagined it.

The recreation of the first real test of the bomb is beautiful and frightening and was profoundly affecting.

Oppenheimer was dogged by controversies all of his life.

Anti-communist attacks nearly ruined him, as well as the friendships and romances that both sustained and threatened him. He wasn’t built to ban Communist scientists and lefties from his life or his work, and his long-running affair with an outspoken Communist activist gave the FBI and the government’s Commie-haters lots of ammunition after the war. His security clearance was revoked, so he could no longer continue his research at Princeton. Once a grateful country, politicians turned on him on a dime.

He could never work in the government again.

Nolan got me dizzy at times by moving the chronology around.

It’s almost impossible to keep up with the scientific and Hollywood stars Nolan brought into the movie. Kenneth Branagh plays physicist Niels Bohr, a vital Manhattan Project research group member. Nolan has loaded the film with celebrities, many of whom come too fast or are too well disguised to be recognized; there were so many it was distracting – Matt Damon, Robert Downey Jr, and Gary Oldman. Even Albert Einstein made a few appearances.

Nolan chose to refer to almost every part of Oppenheimer’s life and development as a scientist – Germany, Berkeley, Princeton, and Los Alamos. Oppenheimer was an old-style liberal: he supported the fight against the fascists in Spain; his brother was a member of the Communist Party, and so was his girlfriend; we see him laying the mines that would come to haunt in the McCarthy era as he struggled to adapt to post-war life.

(Techies: Cinematographer Hoyte and Hoytema shot the movie in 65-millimeter film (projected in 70 millimeters, a dazzling effect that can only be seen in a handful of American movie theaters.) Nolan integrates the black-and-white sections with the color ones. I understood what he was trying to do, but it sometimes made me dizzy. The film feels like jumping around until the end when it goes too slowly.)

The black-and-white scenes define the last third of “Oppenheimer,” and they slow it down. To me, this was the movie’s only mistake. It felt like Nolan got too caught up in the Communist witch-hunting of the time; the attacks did not obliterate Oppenheimer’s achievement or wipe out his place in the history of the world.

But his public concerns about the war angered President Truman (never a thoughtful man), who had ordered the bomb to be dropped.

As a result of hoary Washington politics, Oppenheimer was subsequently portrayed as a Communist Bogeyman by the government he helped save. It didn’t need a full hour to make that point. His mistake was in arguing repeatedly that nuclear weapons should be in the hands of the United Nations, not individual countries.

One of the film’s most touching moments for me was the sight of Oppenheimer reciting the famous words that crossed his mind as the mushroom cloud rose in the New Mexico desert:

“Now I become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

For me, that was the spiritual center of the movie, a wrenching and perhaps even prophetic reality about the impact of science and technology in our world.

It doesn’t have to be a horrific bomb to unravel our society and culture. Just look at the Internet. After seeing the movie, I was haunted by the terror and uncertainty plaguing Oppenheimer for the rest of his life:

Had he helped save the world or made it possible to destroy it?

I loved the movie, was fascinated, so didn’t mind the 3 hours, but I admit, read the long WIKI page after seeing the movie, science never my strong suit. The only scene questionable, the 🍏, might never have happened, but was fun dramatically.

was waiting for your review, Jon…and I wasn’t disappointed. ANY 3 hr. film is more than I could endure at a theater…so I probably will not see it until we can stream it at some point. But……I am familiar with the Manhattan Project and the inner turmoil that surrounded everyone involved for the rest of their lives (not to mention what the world experienced as a result). We feel fortunate to have met Frank Oppenheimer in 1981 at his Exploratorium Museum in San Francisco but it was not an intimate meeting……it was a gently courteous bow and a heartfelt and warm handshake. There was a sense of reverence (for lack of a better word) for a human being that could participate in imagining, designing, and *creating* such technology. I DO hope to see the film at some point……..thank you for your review and commentary.

Susan M

Thank you for your review. I haven’t seen the movie yet, but plan to see it soon. Your review has given me a little advance preparation for it. Having been a child and teenager in the 1950’s in Oak Ridge, TN, where the huge plants refined the nuclear fuel, “the bomb” loomed over my life while I was growing up. Like many children, we had school drills where we hid under our desks in case of nuclear attack. As children, we had no real sense of how pointless that exercise was. Like you, I may have to watch the movie more than once to get all of the nuances, although I’m not sure my nerves will be up to it!