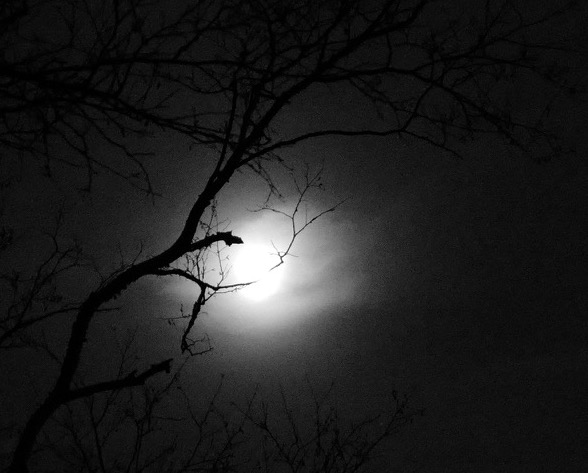

(Moon over Bedlam, Tuesday night, above)

Moise and I were supposed to go pick up his daughter Delilah at the Albany Train Station. She’d been away for seven weeks, helping her sister move from one house to another in Maine.

Moise had to deal with concrete suppliers bringing concrete for him to pour into his new house. So Moise’s wife Barbara came with me instead. I love riding with Moise, but I was glad to spend some time alone with Barbara; she is so busy every minute of the day that I was looking forward to talking to her in more than bursts.

I read her the piece by an amateur sociologist that I was going to show Moise about the idea that the Amish are growing so rapidly in numbers that they may take over the country one day.

“What do you think?” I asked her.

She laughed out loud and looked at me as if I had just escaped from a mental institution. I could almost hear her thinking, “why on earth would we want to do that?”

We moved on. Barbara was open, interesting.

She talked about her trips to Mexico, where many Amish travel (by train, they don’t fly) to get medical care.

They all say the doctors are excellent, the first-rate health care, and the prices are almost shockingly low. I doubt these are the doctors poor Mexicans get to see.

She talked about their lives in upstate New York and their happiness living here. Barbara is a gentle, simple person. She has a big heart and a generous spirit. She has 14 children (one died) and has 11 grandchildren.

She is 50 years old. She appears in good health but has pain in her legs. She sees a chiropractor often.

She asked me about my foot operation and she always asks about Maria and wants to know what she is doing. I always tell them, but I get the feeling they can’t picture a fiber-hanging painting.

She thanked me for the flowers (mums) brought her the other day. She loves flowers, but they are not the kind of thing the Amish would buy for themselves. I make it a point to give her some.

I was interested to see that Barbara doesn’t have an easy command of English; she mostly speaks Pennsylvania Dutch and thinks about organizing thoughts in English.

When we got to the train station, she realized she didn’t have a mask or money and had nothing to eat.

I carried an unused emergency white mask in the car, which I gave her, and we went to the newsstand, where she picked out an ice cream sandwich and a candy bar.

I also got her a bottle of water.

As always, she insisted on paying me for the things I bought when we got home. It was easy talking with her. I know she’s probably forgotten by tomorrow morning; her day is so filled with work and activity.

She’ll probably make me take cookies or a pie or some zucchini bread. I won’t accept their money, but I will take some zucchini bread, which Maria and I love.

Amish women don’t spend much time with men outside of the family, but I think we were both at ease. I’ve seen her and talked with them nearly every day for months. Her daughters call me “grandpop.”

We aren’t very formal with each other, even though she can barely comprehend anything about my life. The conversation flowed naturally all the way to Albany (an hour and a half); there were several long and comfortable silences.

When she stopped talking, so did I. The Amish are very comfortable with silence, and so am I, even though I talk a lot more than they do and ask many questions.

I enjoyed her very much, and I was interested in seeing how her world revolves around family and community. And she has a lot of family to keep up with. She loves every one of them.

We thought Delilah’s train would be late, but Barbara, who has had a lot of experience traveling (she just got back from an Amish wedding in Minnesota), got up and walked around. She did some detective work.

She reported back that she heard a training coming in (it wasn’t on the board) and ran into an Amish man, who happened to be her brother-in-law, who she had not seen for three years.

They were both pleased to see each other in their reliably low-key way.

No shouting, no drama. This is Gessenheit, the Amish code of calm, simplicity, and softness. You don’t get excited, and if you do, you don’t show it. The only time I’ve seen Moise lose his cool is when he’s plowing dirt in a field, there is joy written all over his face.

In addition to her reserved excitement at running into a family member like that, Barbara looked down the platform and saw Amish people coming up the stairs. The train had not been posted on the digital board. Barbara felt it come in.

Delilah, who she had not seen in nearly two months, was one of the passengers coming up the stairs, hauling a huge and heavy suitcase. She walked right past her mother, noticed her in conversation, nodded at me, and sat down when she saw Barbara wanted to talk to her brother-in-law.

I was surprised. No hugs, kisses, exclamations of joy, no show of emotion at their reunion (I do know how much these two love one another, I’ve seen it a hundred times).

I asked Delilah about the trip. She said it was fine; she enjoyed it. This was, she said, the longest she had ever been away from home.

She had her travel bonnet on and looked quite mature (16) in her dignified and beautiful travel clothes. There’s a sharp fashion designer somewhere in the Amish world.

Delilah sat in silence until Barbara was finished talking to her brother-in-law.

Then Barbara came back to us, we all went to the restroom.

Delilah insisted on carrying her luggage, and up to that point, I had not seen the two touch or speak to one another, still no show of emotion or affection. I remember showing more emotion to my daughter coming home from school in the afternoon.

When Maria and I are apart for a day or so, there is much rejoicing when we re-join one another, many declarations of how much we missed one another. It’s pretty sappy, actually, but very genuine.

When we got to the car, Barbara asked me if I would mind her sitting in the car’s back with Delilah. Of course not, I said, you haven’t seen one another in a long time.

Barbara slipped into one side of the back, Barbara another.

From the minute the car started, the dynamic changed. Barbara and Delilah broke into Pennsylvania Dutch, the language they all speak at home, and they never stopped talking, laughing, sharing stories until they got home.

If you ask an Amish person whether or not you can get something for them to eat, they will say no, at least once, perhaps twice. If you ask them the third time, they will often say yes.

I was interested in the conversation in the back seat, which showed to people who were very close, had missed each other, and had many stories to share.

I could sense Delilah bringing Barbara up to speed on moving her sister, Barbara’s daughter, and I could make out Barbara filling Delilah in on all the family news (which I won’t describe here, as they weren’t telling it to me.)

I was ravenous when we got to a convenience store – the Amish love Stewart’s – and I asked three times if Barbara or Delilah wanted anything to eat. On the third round, Delilah told Barbara that she was hungry. Barbara asked me if I would get Delilah an ice cream sandwich.

I asked Barbara if she wanted one, and she said no.

There’s something about how the Amish are level with one another, no highs and lows to alarm or confuse. What I saw in the car was how they love each other, are private, quiet, and very real.

Then I asked again, and she said yes, thanks. “But I’ll pay you back when we get home!'” she said. I got myself a slice of pizza and the two of them giant-sized Ice Cream sandwiches from Vermont.

They were grateful for the sandwiches; they ate every inch while continuing to share how they spent their time apart from each other. I think they were up to date when we got to the farm.

Barbara asked if Maria might be worried about me; it was getting dark. I looked up and saw the bright moon and said I would be amazed if Maria were not out on the back porch looking at it when I pulled into the driveway.

At the farm, their temporary house was black; I could see the kerosene lights flickering inside. Barbara, who was tired by now, insisted on paying me back; I said, no, we’d talk about it tomorrow when I brought the ice cubes. Okay, she said, but don’t forget. I won’t, I said.

Two of the grandchildren came rushing up, clapping their hands and dancing with joy. They have not yet been taught Gessenheit, the calm at the center of the Amish emotional universe.

You can feel all you want, but you also learn how not to show it.

Their reserve is not about being cold or failing to love one another. It is all about loving one another and how it is shown. There is a calmness and peace to their lives. It centers and sustains them.

It would be difficult individually, but my plea to the universe is that our society and our media could be touched by a spirit of Gessenheit.

It does seem to work…

I am from Thomasville Georgia. I have been in Cambridge visiting a dear friend and I have had the privilege to meet this wonderful family. Most of the time I interact with Barbara, Fanny, Leena, Barbara, Delilah and Sarah. I have learned a lot about their simple ways and I so admire them. I treasure their friendship. I’m going home Monday and I will truly miss my Amish friends. I hope to hear what’s going on through you Mr. Katz. They told me that you put things on FB so I hope you don’t mind that I requested your friendship.

Happy to have you as a friend, Marcia I’m glad you got to know these lovely people, I will keep writing about them and annoying them with my photography…I love our friendship…Stay in touch.

Beautiful story. So much to learn about the Amish way of life.