It’s been raining heavily for some part of every day, but every time I come by Moise’s barn-raising, a huge amount of work has been done. They just keep going.

Every day is long, dirty, hot, wet, and hard. I sometimes feel guilty of watching other people work so hard, but there is not much help I could offer them, even if I wanted to.

They’ve poured concrete for all the interior walls of the new barn, which will contain farm equipment, tools, sheep, and goats. They’re now building a rise in the back of the barn, another big concrete wall.

When I arrived, Moise and the workers were up on the hill pouring concrete. I don’t take any photos during the raisings when I am close to people, but the barn itself was clear of workers.

Moise and Liz Willis have both signed off on buying sheep.

Moise wants 20 lambs and ewes, Liz agrees to sell them for $150 each. She is pleased.

Liz initially wanted $100 (she took them in as a favor for a sick friend, she needs to move them out), then thought about asking for $200; we all agreed on $150 to be fair and come together in the middle.

Liz is very relieved about the deal, and Moise is also happy.

It’s a good price for healthy Vermont wool and meat sheep.

It’s rare in a negotiation to make everybody happy; Maria (she was in on the negotiations; also, Liz is a good friend). It was good for everyone, she wanted to sell the sheep, Moise wanted to buy a flock.

I appreciate that while Moise drives a hard bargain, he also drives a fair one. I’m proud of the deal we struck.

Despite the wet weather, the work on the barn continues, with about 12 to 15 workers, mostly family, coming in half the day.

By the end of the month, between 75 and 100 Amish workers will be on hand to raise the barn roof. That is the actual “raising.”

They will be staying in nearby farms and barns in a huge loft the Millers have created in one of their existing barns. Moise is working from dawn to dark, rain or sun; I honestly don’t know how he does it.

We waved to each other, but I keep a distance. I don’t want to interrupt; there’s too much to do. My thumb wrestling has become a thing; all these strapping, muscular young Amish men come over to me with their thumbs out.

I was massacred, I won two rounds out more than a dozen, and I have a sore thumb to show for it. Fanny and little Sarah cleaned my block as well. I am getting older; the Amish have mighty thumbs.

I brought three bags of ice cubes up to the house this evening, and Delilah asked if I could order two more boxes of pie pans, they are on the way.

________________

I was thinking today about the Amish school being set up on one of the Amish farms. It will probably be in a barn this year, with a single teacher.

This is a subject I stay away from; I sense it is sensitive and difficult for the Amish families. to talk about, one of the few times they are not at ease answering questions.

The Amish do not need donations or money for their schools; they have publishing houses that print their own texts – Psalms, the Lord’s Prayer, German hymns, English hymns, and financial resources.

The schools use flashcards for the first and second grades to practice math, while the seventh and eighth graders calculate percentages and the diameter of a circle.

Older students help the younger ones.

In 1913, half of America’s schoolchildren attended a single-teacher school, much like the Amish schools. Just fifty years later, the percentage of one-teacher schools was down to one percent.

Small schools were merged into larger schools; by 1928, one-room schools were closing at 4,000 a year.

States began setting standards for teacher education; legislatures began increasing the length of the school year and the number of required years and expanding the size and curriculum of schools.

There was a national commitment to compulsory 12-year education, the ideology being not about religion but the idea of American progress that promoted schooling for citizenship in a democratic society.

The schools were designed to promote the American ideal as well as teach English and math.

This put the states and the new education system on a long and painful collision with the Amish church, the worst in their history here.

The Amish schools only go to the eighth grade so their children can work on their farms and businesses and be with their families. Needless to say, the fundamentalist Christian ideology of the church is very different from the public school curriculums.

The Amish do not want their children taken from small and intimate schools and sent to public schools, where there were compulsory attendance laws and where religious education was forbidden.

As one-room schoolhouses closed across America after 1900, the clashes with the Amish were inevitable and not long in coming.

The first was in 1914 in Guaga County, Ohio, where three Amish fathers were fined for refusing to send their children to ninth grade.

In 1921 eleven fathers were jailed in northern Indiana for withdrawing their children from ninth grade, and more were imprisoned three years later.

By 1937, the Amish fight for control of their one-teacher schools had spread to Pennslyvania, Ohio, Indiana, Iowa, and Kansas.

By the late 1960s, it had spread to Wisconsin; scores of Amish parents were arrested and served short sentences in prison.

More than 125 parents were arrested in one Pennsylvania township, some as many as a half dozen times.

Two struggles – one in Pennsylvania in 1937 and another in Iowa in 1965, brought the Amish struggle into the national spotlight. The New York Times published twenty-three articles about the Amish between March 1937 and December 1938.

Thirty years later, a school conflict near Hazleton, Iowa, touched off a national furor when a photo of Amish children scampering into a cornfield to avoid being bussed to a consolidated school was published and reproduced all over the country.

A group of scholars, religious leaders, and lawyers founded the National Committee for Amish Religious Freedom and took the Amish case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The committee won the first in a series of ruling support of the Amish right to school their children in their own way.

The major fear of Amish parents was – and perhaps still is – that modern education and modern technology would lead their children away from their faith and undermine the structure of the church, which had held Amish communities together for five hundred years.

In Amish schools, according to the book The Amish, the church community depends on a practical education in which wisdom is acquired through sharing labor, learning responsibility, interacting with older members of the community, doing chores, and listening to conversations on their farms during meals.

Amish school, says the authors of the book, prepare their children to write letters, read newspapers and do the arithmetic to pay bills.

The purpose of education, says one Amish bishop quoted in the book, is to prepare them “to live for others, to use their talents in service to God and Man, to lie an upright and obedient life, and to prepare for the life to come.”

The Amish parents I’ve spoken to say they can’t imagine sending their children to public schools. I admit that I can’t either. Several different court rulings have supported that position.

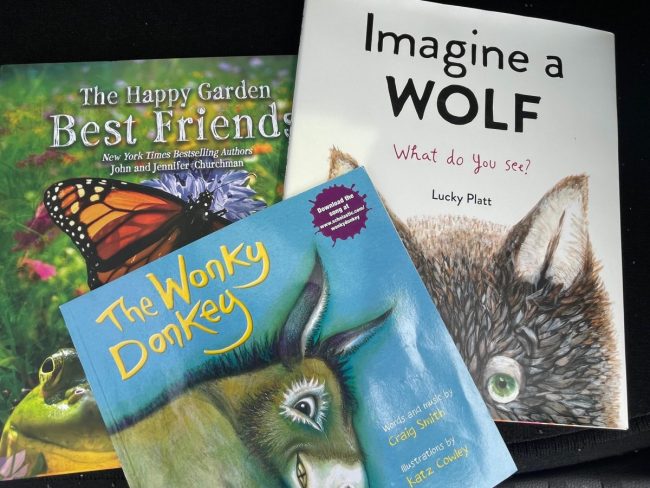

There are several very young children on the Miller farm these days, and I offered to pick out a small number of children’s illustrated books – mostly about farming and animals – and the family said that would be welcome.

That will help them prepare for school in a year or so, they say.

I brought three books them over to them today:

Otherwise, I sense that the Amish community very much remembers the issue’s sensitivity and long and bitter struggle.

No one is asking me for help with their school, and I’m not offering any. I think they are gracious about accepting books, but I also know their curriculum is rigorous and is intensely guarded.

It is still a very personal issue for them, their greatest fear and worst conflict with their new country – that they will lose control of their children’s education to a secular curriculum.

This, they say, is tantamount to the destruction of their community.

Many Amish mothers and fathers paid the price to save their schools and maintain their own notions of education. For a community taught to avoid conflict, it was a hard time not yet forgotten.

The new school feels like it’s not really my business. If they need help, they will ask for it.

They need ice cubes and somebody to order things online for them right now. They don’t seem to need or want people to get involved in their children’s education.

That feels right to me.

Since writing about the Amish, I’ve learned how angry many people are at their stubbornness about being different.

We pretend to be a tolerant and inclusive country.

My e-mail this Spring has reminded me that we are not.

The Supreme Court ruled that the “enforcement of a state’s requirement of compulsory formal education after the eighth grade would infringe upon the free exercise of (Amish) religious beliefs.'”

The practical consequence of Yoder vs. Wisconsin in 1972 settled the legitimacy of Amish schools.

The practical consequence of Yoder, wrote Amish scholar Donald Kraybill; it also permitted Amish youth to continue o enter apprenticeships when they turned fourteen. By 1985, the number of Amish schools had more than doubled to nearly six hundred.

By 2005, Amish scholars estimated the number of Amish schools had risen to more than 2,000.

For me, much of the draw of the Amish story has been about our willingness to accept the different and the “other.”

The Amish don’t seem to spend much time worrying about us and our values; they just want to be left alone to define theirs.

Given the awful and bitter divide in America today, it’s hard to believe we can’t learn something from them about that.

Long live the differences.

Jon two really good kindergarten level books are “Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What do you see?” by Bill Martin Jr and Eric Carle, and “the Very Hungry Caterpillar” by Eric Carle. I used both of them when I was teaching, and the kids loved them.

Thanks Cindy..

I am a huge fan of “Shall I share my ice cream?” by Mo Willums for the little ones. It is like their first moral dilemma and you can just see the wheels turning as they try to puzzle out what to do. I think it would pass Amish muster.

Great idea…

I very much enjoy your writing on the Amish. If I have anything else to say I’ll write you a letter but it’s summer and I do letters in the winter.

OK

I continue to be in awe of the barn raising construction. Thanks, Jon, for keeping us apprised each day. Even though your photos probably fail to capture the enormity of the undertaking, they clearly demonstrate the engineering and sophisticated design of the structure. In our “English” world, the massive concrete walls and piers would have been filled by massive concrete pumps fed by a line of ready-mix trucks – to acknowledge and understand that all of this work was done by manual labor is simply an astounding accomplishment. My hat is off to Moise and his crew for this remarkable engineering and amazing undertaking. Again, thanks, Jon, for your daily reports!

Thank you for continuing to share information about Amish culture. Religious freedom is a gift as long as it not used to persecute others. How does the Amish community handle issues of their own members who identify as LGBTQ? Is there any tolerance of diversity? What do they think about inclusion? As an educator, I worry that the community will not be able to sustain themselves when technology takes over our lives completely. Look how you, the writer are able to share your thoughts with us-through technology. How will the culture survive if their children cannot learn to design a computer or operate one? Will the surrounding cultures always be so cooperative? The future of farming will be affected by climate change and how will that alter their lifestyle? There is an irony there in that they rely on neighbors and business partners to accomplish their goals. What do their teachings say about that? Technically, they are living in the 21st century by proxy.