Tonight, I had a much better story to tell than a dismal nominating convention. My story is about hearts and selflessness and what it really means to be a human. Behind every act of giving is grace.

Drawn as we are to the dark and cruel side of people, it is so easy to forget how good people are, or that angels walk among us, washing away our hate and selfishness, showing us the true promise of being in the world.

When I lay in my hospital bed, eight or none hours away from my surgery, exhausted and worn down by my day, I looked up and saw a young nurse, her name is Julia Spelter. She works at Saratoga Hospital, and she had blonde hair and was thin.

She was looking at me, she had something on her mind to say to me.

I had been listening to her sweet voice for nearly two hours now, lying in my dark half of the room, looking for some spiritual trick to get through the night.

Julia was only a few feet away from me on the other side of a thin curtain dividing me and my dying hospital roommate. The curtains offered the illusion of privacy while, in fact, taking it away.

I had been listening to this stranger – a nurse, I could tell – living in grace and warmth and love as she tried to comfort my very ill roommate, never losing her patience, her kindness, or his dignity.

She soon enough had me crying, just over the beauty of listening to her, she was entering into one of the most beautiful and selfless things I had ever witnessed.

And how surreal. She couldn’t see me and I couldn’t see her. I just heard the gentle, soothing voice. Now, she wanted to say something to me, she knew I was there too.

“I wanted to apologize, Mr. Katz,” she said as she peeked around the curtain. “I know you’ve had trouble sleeping all night, and just when you started to go to sleep, I woke you up didn’t I?”

She was soft-spoken and confident, I could tell she wasn’t really sorry, she was just sorry for me.

I didn’t want her to apologize to me for doing something as beautiful and loving as she had done.

I tried to sit up, which I was forbidden to do for at least 24 hours. I wanted to thank her for what she had done for the sick old man.

“No, no,” I said, “It would be devastating for you to apologize to me, after listening to what you have done for this man tonight. Please tell me your name so I can write about you or at least write a letter to the hospital telling them what you have done tonight. It moved me greatly…”

She nodded and said I was kind and then smiled and disappeared, she had left the room. She wasn’t looking for praise.

Her voice haunted me, I called Maria at 4 a.m. to tell her this story. “She was an angel,” I said, “she had to be.” I had rarely in my life seem so much patience and empathy.

She never lost her tone of concern and respect. I thought of how little empathy any of us see in our world of anger and cruelty. How hard it must have been, I thought, to do that in silence, with no response or chance of response, no kind of gratification.

I didn’t see her again during my stay but the other nurses knew who she was right away and gave me her name. They knew who she was the second I described her.

Aesop said that no act of kindness, no matter how small, is ever wasted. She had made this very sick man comfortable, at least for a while. For a few minutes, he could breathe peacefully. Then the coughing came back, it was a awful sound.

I am to think that he heard the sweet music she was making with her kind words.

While Donald Trump and his friends postured and preened, this gentle sprit put aside the ugliness and sometimes even revolting reality of this man’s life and talked to him and kept talking to him. There was no video camera on her, no Tik-Tok cameo, no CNN hero story.

There was no interaction or any kind of response, how much strength would it take to hold a conversation like that?

This man, at the very edge of life, was a kind of hero to me, and so was she. There they were, out of sight, one struggling to live, the other struggling to live well.

The old man didn’t seem to be hearing Julia, although she assumed that he was, as every hospice social worker always does.

Just assume they can hear you, the social workers used to say. Don’t talk to them like they are children.

____

In my tiny hospital bed – my feet hung over the railing at the bottom – I had hours to kill and nothing to do. The morning was far away.

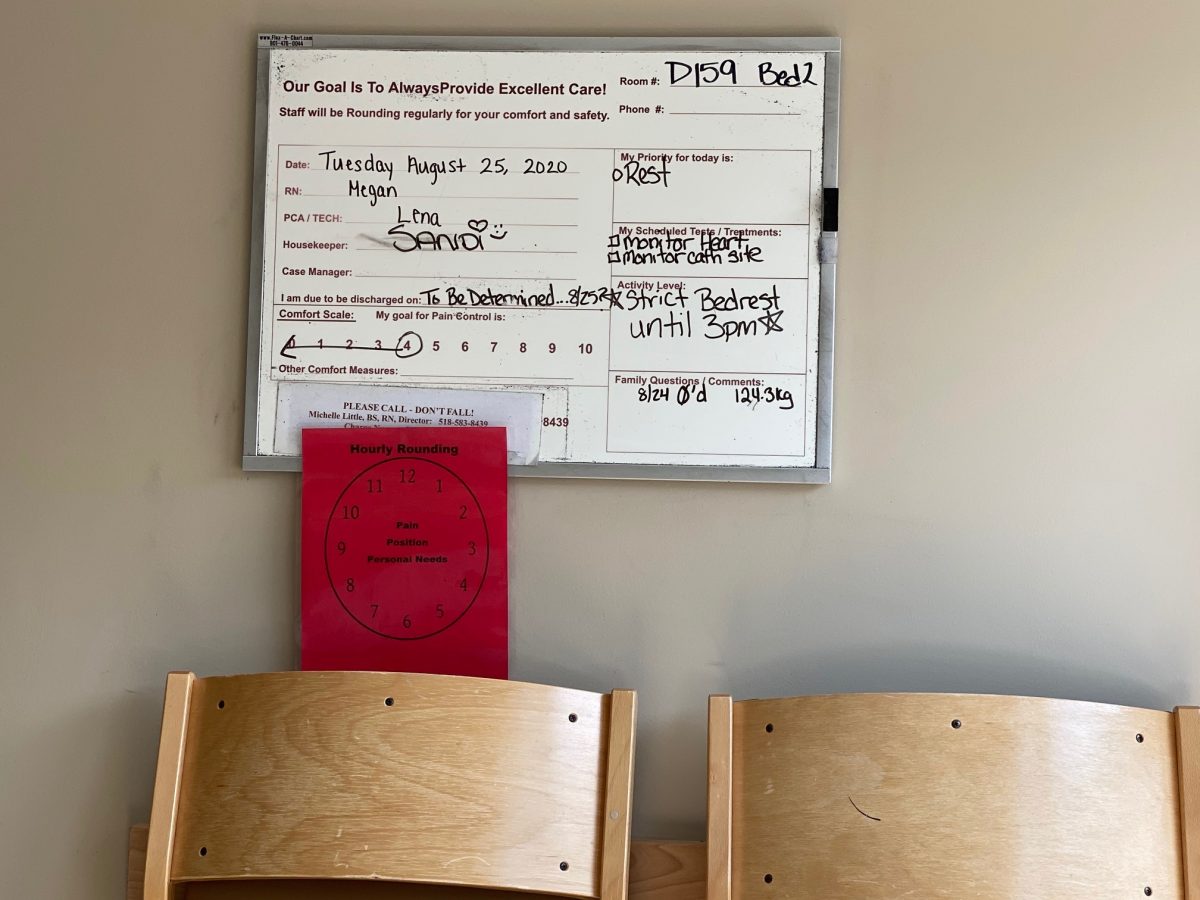

I was feelingly lonely – I missed Maria, I hadn’t brought a charging cord, my cell was running out of juice. Yes, I was feeling sorry for myself. I had had catheter surgery in the morning and it was like a stab in the stomach to turn around in bed. I had to stay overnight so the doctors and nurses see how my injection wounds were healing.

I think it was, in many away, one of the longest nights of my life. I was in considerable pain and the man next to me was tearing my heart to pieces. I always told my sister that she felt too much. Is there such a thing?

Maria couldn’t visit, I had nothing left to read, I wasn’t ready to watch the Republican Nominating Convention, which, on top of everything else, appeared quite boring to me. It looked and felt dreary.

I was starting to feel some self-pity.

I was right next to a man who was gravely ill and was almost certainly dying.

He was hacking in the loudest and most awful way I had ever heard or seen, much more like a wounded animal than a human.

It made me slightly nauseous at first, the sound and the smell, and I wondered if I should try to help, but I didn’t.

There was no chance of sleeping and he sounded so awful I could hardly bear to think of the pain he was in, or how to help him.

The poor man was unconscious, even comatose.

His face was stretched thin in the death rictus so tight that his teeth protruded, almost like a skeleton. He never opened his eyes or even blinked.

Two or three times that night I whispered “hello,” through the curtain, but he never replied.

I had seen that faces in my hospice work, it was a death mask.

I got up and peeked around the corner before my alarm went off to see if I could say hello to him. He didn’t hear me or look at me, just coughed and coughed the deepest cough I had ever remembered hearing.

I tried asking him if he was okay. He didn’t respond or open his eyes.

I went back to bed and was almost hypnotized. There was nothing I could do but listen to Julia when she appeared. I could not imagine how to help this man.

The nurses were taking buckets of liquid out of the small room, whatever he was coughing up never seemed to end or, and it wasn’t clear if he could hear anything they were saying to him.

It seemed there was almost always someone coming into his room to try to help him. But the hacking never once stopped until Julia was done, and then only for a few minutes.

I never heard him utter a word or answer a question.

I could not imagine how this frail old man could cough up so much liquid and keep going.

I thought he couldn’t speak and couldn’t stop trying to cough up what kept coming out of him. One after another, the nurses came. They siphoned off the phlegm, said hello, soothed, and tried to comfort him.

After a while, I just got used to this sound, which came just a few feet from my head on the other side of the thin curtain that divided us.

I knew I could never sleep in that way, so I just listened.

I thought of Mother Teresa, how she would have been cradling this poor dying man in her arms and washing his feet.

Give your hands to serve and your hearts to live, she said. Isn’t that why some people become nurses?

I pushed the call button, still groggy from the sedatives they gave me to knock me out, and went and stood over the urinal I was given.

They were using the bathroom to take care of what the man was coughing up in this awful hacking.

A young nurse came up to stand behind me, and I knew my butt was probably hanging out of the skimpy robe I was given. “You don’t need to see this,” I said, embarrassed.

“Oh, don’t be silly,” she said, “I see it all the time. It’s what I do.” I went to the bathroom, the world didn’t come to an end. She really didn’t care. It is good to be humbled.

I startled myself by suddenly asking one of the nurses if I could help with this man when she came in to take my “vitals.” It just seemed so strange to be lying there.

She smiled and said no, I should stay in bed.

Because of the man’s awful and loud choking and hacking, the frigid temperatures in the room, and the strict orders I was under to not stand up for at least 24 hours by myself without a nurse alongside, I felt imprisoned, useless, almost claustrophobic.

I stopped fighting it. I just lay in bed and tried to meditate, and listened.

What I heard mesmerized me. Julia was talking to the old man, she called him “Mr. L.” She seemed to have come in just to make him more comfortable.

“I’d like to help you,” she said, or “I know this must be so uncomfortable, Mr. L. I’d like to make this more comfortable for you,” she said, over and over again.

He couldn’t hear her as far as I could tell, and he never responded, but he let her use a siphon and a bucket over and over again, even as he ignored her requests so sit still, co-operate, and to open his mouth for her. I guess he did because I heard the containers fill.

Julia never once showed any impatience with him, even though, for what I could hear, he never once thanked her or acknowledged her patience. This will help you, she said, let me help you, are you okay?

Lying there in my bed, I felt my self-pity and lament and complaint melt away like an ice pop in July.

I was riveted to the sound of that sweet, soothing and polite voice, talking to over and over again, helping him clean out his lungs with siphons and buckets, and clothes and those sweet, sweet, words.

It was a meditation, a better angel at work. She was singing a beautiful song, and it touched me so deeply.

Thinking of the news, I thought, it doesn’t have to be this way. There are so many people eager to do good.

Julia was a child of Mother Teresa to me, indifferent to the smells and the mess and the phlegm and the hacking cough, disinterested in the news, the argument, the nasty messages, and the lies.

We make a living by what we get, Churchill said, but we make a life by what we give. How wonderful it is that nobody needs to waste a single second before starting to help another person or starting to improve the world.

When people complain to me about politics, I often wonder: what are they waiting for?

My discontent was gone now, I was humbled and filled with gratitude. I woke up.

What right did I have to feel sorry for myself because I was bored in a hospital bed? How lucky and I, I thought not to be coughing my heart out waiting to die?

This is what an angel does, I thought as Julia came out from Mr. L’s bed and waved goodbye to me. I asked her for her name, but she was too shy, I wanted to thank her but the didn’t need that.

There are angels in the world, and I had spent an evening with one in a hospital in upstate New York.