I knew a day or so ago that my friend Ed is mostly gone already.

He is different, struggling, exhausted, his cancer is chewing him up day by day, it is all over his face. He seems spend. The Ed I knew isn’t there much of the time. I have been saying goodbye to him for awhile.

When a friend is dying, it seems to be a great responsibility to help him in any way he wishes.

We and the Gulleys are important to one another, we have changed each other’s lives in many ways, Maria and I will not walk away from Ed or Carol. My afternoons with him and with Carol are quiet, peaceful and spiritual, and today Ed and I were able to talk honestly and openly for a a few minutes.

Maria was in the kitchen talking with Carol, they have become close friends.

This kind of real conversation was hard for Ed and I to do in recent days. Most of the time, I just sit and read and let Carol nap or do some chores or pay some bills.

I knew we didn’t have long to talk today.

But it was important.

Today, Ed’s daughter Maggie published one of his poems on their blog, the Bejosh Farm Journal, earlier today.

“Why do the millionaires get to walk?,” asked Ed in his poem.

“I’m just a poor farmer.

Why can’t I walk?”

Like several of Ed’s recent poems, I recognized this a cry of anguish and frustration. In a very literal sense, it was the cancer speaking, not Ed. I didn’t recognize Ed in it.

“Ed,” I asked while we were talking to one another this afternoon, “do you really believe that millionaires don’t get cancer?”

He smiled and looked up at me.

“No, I know better than that, he said, I’m not that big of an asshole.”

Why did you write it?, I asked. “I don’t know,”he said, “sometimes there’s someone or something else in my mind”

I nodded, I said I understood and I do understand.

He said his great frustration and torment comes from asking others to do things for him that he has always done for himself. He feels ashamed and at night mostly, believes the cancer is punishment for failing to do good in his life.

We talked about that, and I don’t need to repeat those words here.

Ed asked me if I thought he would be able to walk again. I said I didn’t know, it wasn’t for me to say. But I saw the anguished look in his face, and I knew I had to speak honestly to him.

I said we had never lied to one another, I was not about to start now.

“Listen,” I said, the kind of cancer you have doesn’t give things back, it takes them away. It doesn’t go backwards, it keeps moving forward, it is ferocious. I don’t believe you can bull your way through it. I can’t say you won’t walk again, I can only hope you aren’t fighting the reality of this. I wish for you to find some peace and I have the sense you are fighting the cancer every minute, trying to outsmart and outmaneuver it. You keep saying it’s like chess. Your left leg isn’t working any longer, and that makes it hard to walk. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try, you should do whatever you want to do.”

But you know by now, I said, that you can’t outthink it or outfight this kind of cancer. It isn’t really like chess.

I reminded him that we both talked about this the other day, “it isn’t a war,” I said, “your home is not a battleground. The cancer will do what it will do, I just wish that you have some peace at this time, I hope you make peace with yourself rather than prepare for battle. You deserve it.”

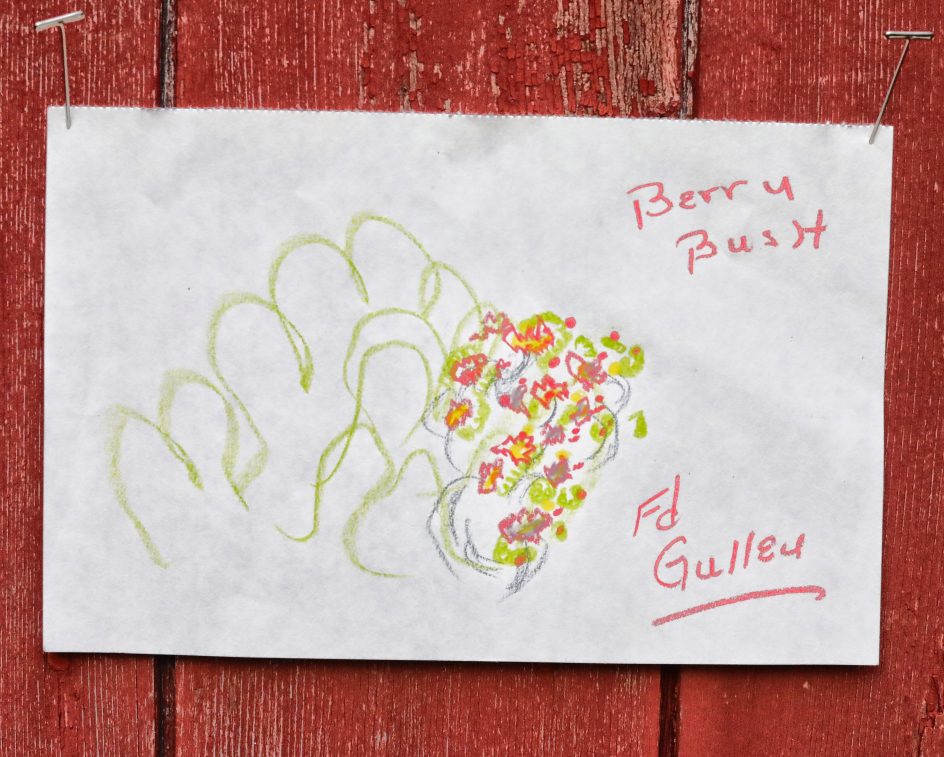

He said he is most peaceful when he is sketching or drawing.

I recalled a poem of Ed’s that Carol published the other day, “mind power is of the utmost importance,” Ed wrote, “you must face it with your mind, you must pass this test…”

I asked Ed if he thought this cancer was a test he had to pass, a battle of the mind, and he said yes, sometimes, that was the way he had always looked at life. He had to be strong, he had to be tough. He had to figure it out, and for himself.

Maybe, I suggested, he could think of a gentler story for himself.

I told him I was going to be honest with him, as he had asked me to be. I reminded him he had asked me to shout loudly if he showed self-pity. I said I knew he wished to be open about his cancer, and that he had asked Carol to do the same.

But I said I didn’t recognize him in some of those poems, I had never heard him utter an envious or angry or self-pitying word. I knew the cancer put some thoughts and emotions in his head, but I am not comfortable quoting or writing about or photographing a different Ed Gulley than the one I know and love.

I just wanted him to know that.

I would only take portraits of his face in repose or thought, I didn’t think it proper to do any more videos together, and I wasn’t comfortable publishing or quoting from poems or pieces that I knew did not reflect him and what he has always believed.

The truth is that there is no envy or self-pity in you, I said, I need to point that out.

I said what Carol did about this was her business, not mine, and I knew she was honoring his wishes to be forthcoming and not sugar coat the truth. That was up to her, of course, I said. She is profoundly faithful to Ed, she loves him so dearly.

And one thing I believe: There is no right way or wrong way to deal with this, we each have to find our own best way. We do the best we can for as long as we can.

There are ethics to be a friend and witness to someone’s death, especially someone you care about. I’m not really sure what they are, but I am struggling to figure it out. I’m getting an idea. Death this close is new territory for me too.

I felt I had an obligation as Ed’s friend to protect him from the cancer that was in his head, and that was sometimes coming out in his words and thoughts, at least in terms of what I wrote. I also believe in being open, and I also believe that openness need not be absolute and all encompassing.

I share much of my life, but I also don’t share much of my life.

I told Ed I owed him that, it was perhaps one of the last things I could do for him, and I was certain the Ed Gulley I was talking to today was my friend, and that he was listening and could understand me. I am learning that sometimes, protecting a friend means protecting him from himself.

He looked at me for a long time, and I was not clear what he was thinking. Usually, he would have told me by now. He nodded, and said he wanted to think more about what I had said. “Thanks,” he said, “you are a brother.”

I hope so.

Ed turned away, started sketching. He did two sketches, including the one above.

Then his eyes closed, and he fell back to sleep.