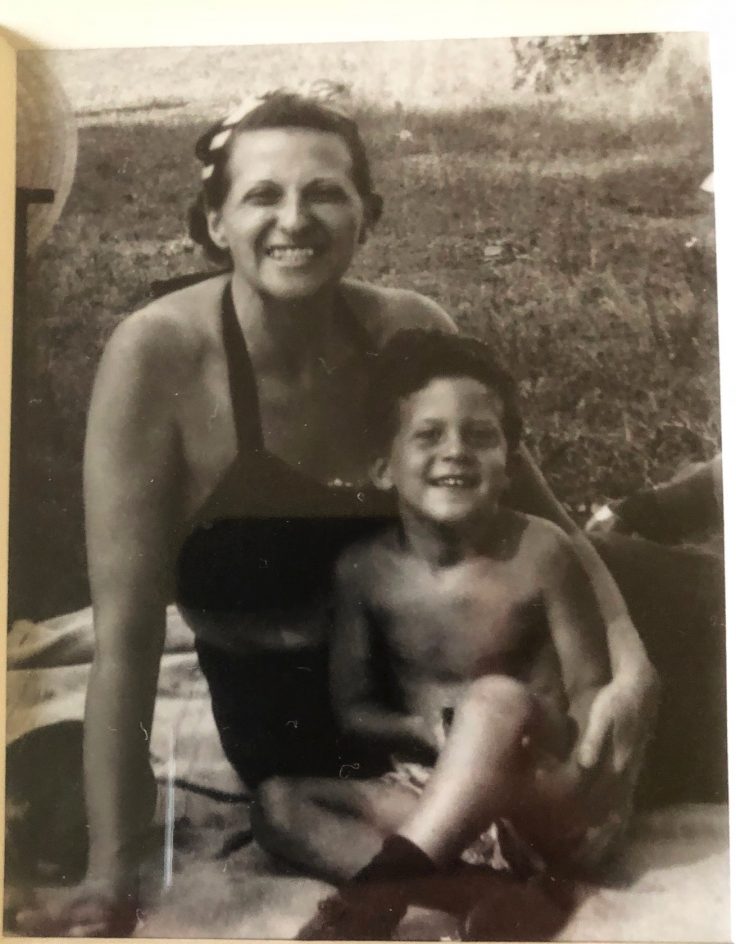

To my knowledge, this is the only photo that exits of me with my mother. I found it in a folder she kept of newspaper clipping of me when I had my 15 minutes of fame.

She was quite proud of me and bragged about me to her friends and sisters. I don’t know who took the photo or where it was taken.

It seems to be an image of two people who are happy to be together, two people who love one another.

That was not the tenor of our relationship. I’ve danced around the subject of my mother for some time, and as I often tell my writing students, there is no point in being coy, it cheats the reader and corrupts the writing. There is nothing more liberating than being honest. Without secrets, I am finally free.

My mother was brilliant, creative, and driven to be independent and successful.

With me, she was incestuous, abusive, and cruel. My sister and I lived in terror of her moods and vicious tongue and explosive moods. My mother could suck the soul right out of you.

She also, I have come to see, loved me a great deal and told me over and over again that I was creative and gifted and could be anything I wished.

I have never been able to reconcile these different parts of her, and avoided her for much of my adult life. I did not see her at all in the final years of her life, and did not see her before she died more than a decade ago. I did what I needed to do. Sometimes you have to let go. Family does not always prevail, that is sometimes cruel myth.

In the photo, which hangs on my study wall, my mother is smiling, and her smile seems genuine, but somehow forced. You can see the immigrant in her face, the touch of Russian.

In the days before digital photography, photographs were expensive and took days to develop, they were often posed and not natural. She rarely smiled.

The boy in the photo, me, looks happy to be there, he looks like the apple of his mother’s eye.

I have only in recent years begun to understand the degree to which men in general and my father in particular, stymied, dominated and ultimately destroyed her many gifts and ambitions – her art gallery, her gift shop, her choices about where to live, her efforts to help my sister, her very spirit.

He never physically harmed to my knowledge, but her spirit died trying to survive her life with him.

They did not love one another, and fought bitterly and constantly. She never accepted being dominated, she never could break free of it. My father was one of those people who loved everyone more than his family. He was a selfish man.

My mother lived mostly in a rage, but always looked for work, fought for her own identity, her own equality and dignity, and lost every battle every time. As a child, I could never understand the depth of her unhappiness and fury at my father, she complained about him to me constantly, and in the most bitter way.

I could always feel her anger, and her many grievances about it, but she should not, of course, put them on me, and I could not bear it, nor could I bear to let my daughter near her.

She told me many times that I was the true love of her life, the one thing that mattered. That is, of course, an awful thing to put on a child. Whenever I visited her as an adult, I barricaded the bedroom door with a chair. The truth is, I see now, that she had no one else to talk to.

Time is perhaps the greatest friend of forgiveness. I believe if she lived today, I would see her as something of a hero, a warrior for an open field in life.

I am grateful to the Me Too movement for several things, but one of them is that the movement – and the struggle for women’s rights that preceded it all through my life – has helped me understand the world she lived in, and the abuse and unfairness that she endured. I’m not sure why, but I think she made the ultimate sacrifice for us – she stayed.

The Me Too movement has reminded me again that women don’t have to be physically assaulted or raped or beaten to be abused. Men have damaged destroyed or smothered woman’s lives in many different ways for all of human history, and that surely sets the table for abuse of all kinds.

There are somethings worse than death, I think.

My mother knew this was all wrong, the way she and other women were trearted, she felt it in her blood and bones, but there was really nothing she could do, she was firmly in the grip of a culture that saw women as always being subservient and inferior to men.

My mother was a victim, her very soul was crushed again and again by the power that men in her world had over her, and over so many other women. There were few good options for them.

I’m not into squawking about the young, but I do believe many younger women have no conception of the kind of world my mother lived in, and perhaps there is no good reason for them to.

They have the right to tell and live their own story, make their own history. The high school principal called up my grandmother to beg her to let her daughter – my mother – go to college, she was one of the brightest students he had ever seen. He was sure she could get a full scholarship.

My daughters will never go to college, she told him, they will get married and have children. My mother never went to college, and the die was cast. She became a secretary and waited for someone to marry and have children with. The idea was not to be happy, but safe.

I asked my mother a hundred times why she didn’t just leave my father, she resented him so much, and she said she couldn’t, she just couldn’t. It was just inconceivable to her, we had all heard the horror stories of what happened to women who left their husbands, they were shunned, left with nothing, shamed. Nothing in her life had convinced her she could do it all by herself.

It just wasn’t done, it wasn’t ever even talked about. My grandmother, her mother, would have died of shame, she said. Just think of a world where your own mother would rather you be miserable and unfulfilled your whole life rather than be free and happy and loved. It was heresy.

As we learn on the news every day, women are still persecuted, often violently, and in so many different ways by then. But things have changed.

My mother did not have the benefit of a women’s movement, or the support of other women, or the idea of female political or business leaders. She did not have a website to turn for help or guidance or support. In her culture, marriage was a sacred obligation, a bond that transcended her own life and wants and needs. Men were simply omnipotent, they always won, they always had their way.

She could rail about it, but not run away from it.

My father was much-loved in our town, he did a lot of good for a lot of people, and my mother said she couldn’t bear to speak ill of him outside of the home, she was faithful and loyal to his public persona to the end, the dutiful wife masking the enraged and suffocating and spirited woman who wanted her own life, and never accepted that she could never have it.

That would make somebody crazy and furious. If she lived in our time, she would have been in the Women’s March for sure, working for the women running for office, or maybe even running herself. She would have had an outlet for her frustration.

She wold be supporting the women who turn to a website for justice and affirmation, and licking envelopes for them. She might well have told my father she wasn’t moving because she loved her gift shop, and wasn’t abandoning it.

She could have said she wasn’t moving because she loved her life, and her own family, she wasn’t going to permit his dragging her off to a strange world, and choking off everything that was important to her.

I don’t think she would have been so angry then, or so frustrated or needy.

I think our story together would have been different, because it is clear to me now that she did love me.

She also gave me the great gift of wanting to create a new narrative for me and wife.

When I married Maria, I swore to myself and to her that I would always support her and encourage her and do everything I could possible do to help her to feel strong and entitled and empowered.

I swore that I would never demean or stifle her creative spirit and fierce individualism.

When I died, I wanted her to think of me as someone who always helped her to live her life, not as someone who thwarted and undermined it.

I’m not dead yet, so I won’t know what she will say of me when I’m gone.

But I think she will not speak of me in the way my mother spoke of my father. So history can change, and is changing, and I am sorry my mother did not live to see it or benefit from it.

I thank the feminists of today and the Me Too movement for helping me to love my mother, and to forgive her. I can stand a bit in her shoes.

My mother had no one to support her, not even her best friend Beulah, who told her over and over again to stop fighting reality and accept things the way they were. You can’t fight the world, she said. Go along. My mother never did go along, and I have to love her for that.

Beulah told me at my mother’s funeral that she believed that you got pregnant when you kissed your husband at the wedding. She had never heard the word penis, and got the shock of her life on their wedding night, she said.

Your mother never accepted things, she said, it made her miserable.

I do love my mother for that. People can squawk and whine all they want, but I am ever grateful that there is a Me Too movement. I know what happened when there wasn’t one.