Every day, I text Ed and ask if he wants to go to lunch.

Sometimes he can, sometimes he can’t. Since he was diagnosed with brain cancer a couple of weeks ago. I’ve been trying to work out what my role is as a friend. I don’t wish to be a hospice volunteer or a man with a therapy dog, or a social worker or amateur doctor.

I just want to be a friend. I just want to listen. I’d like to be there.

I took Ed to lunch today for the second or third time this week, and I realized when I sat down with him at the Round House Cafe – he loves the BLT sandwich there – that Ed and I had hardly ever been alone in our friendship. Most of the time, Maria and I went together to visit him, and when we went out to eat we were a foursome – me, Maria, Ed, Carol.

When we went to Bejosh Farm, we’d go and look at his art, and when he came to visit, he would trek with us out in the woods. I wondered how this lunch would be. It was quiet wonderful, in fact, I am beginning to think we are just becoming close friends in one sense.

In the strange way of men, we had never really made time to be alone together. To build up the very special bond the comes with intimacy and trust. And there is no more intimate experience that the one Ed is going through. We never really got to talk much, we are talking now.

We are often alone together now, and it was special – open, honest, warm and easy. I see what I love about this man, his generosity of spirit, his openness, his honesty, his deep sense of values.

Ed talked about his brain cancer and his upcoming trip and how Carol was taking things. It felt like we have been friends for a long time, the trust and openness was right there, we didn’t have to pull it out.

I asked him why he had stopped farming so abruptly after the diagnosis, he said he simply wasn’t going to do any farming any longer, he turned it over to his children and said he was done with it. I said this startled me because he was so much a farmer, he seemed to me to love every minute of it.

We went back and forth over this, and I watched Ed closely, he seemed better than he was last week, he seemed clear and accepting, and quite lucid. I told him he seemed fuzzy last week, I thought I saw him changing. I didn’t feel that way today.

We talked again about his absolute turn from farming. I knew he couldn’t work at the pace he once did, but why abandon all of it so completely and quickly?

He thought about it, wiping the sandwich out of his beard and hugging friends and passers walking by. Good friends listen to one another.

He said he thought it was probably because he was fearful when he got the news. He didn’t want to know much about the disease and how it would work, he thought he would handle it as it comes. He just had no idea what would happen, so he decided to be safe and do nothing.

But thinking about it, he said, he thought he was just terrified: the reason was that he thought if he did any labor of any kind, he might just keel over and die. He actually did not know how the cancer would work on him, and he was afraid if he did much of anything but sit around and talk and write, it would kill him. The doctors, as usual, discussed symptoms and date and procedures but forgot the part about life – what would happen to him now?

I told him that I had read a great deal about this kind of tumor, and talked to a doctor about, and I urged him to do a bit of reading and talking about it. I said brain tumors don’t work that way, it’s not like having a heart attack, it might progress quickly or slowly, but either way, he would know it when things were really changing, and so would the people around him. Carol would know.

Did he want me to tell him?, I asked, and he said yes, he would like that and appreciate it.

He shouldn’t just sit around if he got bored, i said, maybe go out and do what he can for as long as he can. Do what feels good. He said he liked that idea, he would try it. I think he will. I stopped giving advice, he doesn’t need any more.

We both had the shared experience of doing what we loved every working day of our lives. That is r are.

He said he never farmed for money or milk production, “more than anything I wanted to have happy cows, and if the cows are happy, everything will turn out right. And that’s what happened.” That’s a classic Ed’ism. Make the cows happy and everything will fall into place. Lucky cows.

We had the nicest time talking, Ed said he was also worried about me, he wondered if I was doing too many things, and wasn’t stopping to smell the roses. I said I was surprised to hear that, it seemed to me I wasn’t working hard enough. But I thanked him for the concern and said I would think on it

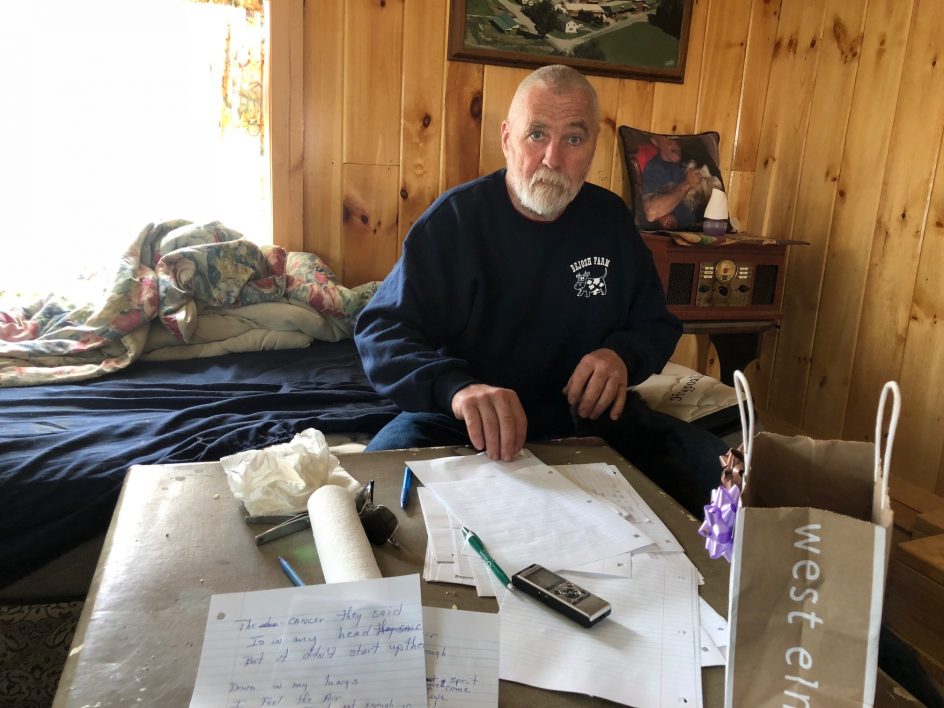

We went back to his house, and we sat in his new lair, where Ed writes poems every day and writes pieces for his blog, and sits with his cats and dogs and holds court with his never-ending stream of visitors an well-wishers. Ed has become a philosopher of the spirit, and of mortality as well.

What’s happening with Ed is sad, but not only sad. There is much beauty and meaning in it, for him, of course, for me.

He loves sitting on a sofa in the room he built, writing poems deep in the night, listening to the sounds of the farm, the radio playing Yankees games, the lowing of the cows, the wind in the drafty old farmhouse, leaving scribbles on notebook paper for Carol to post on their blog..

“I’m at peace,” he said, “I really am.” If I don’t go to Albany tomorrow, we’ll have lunch again. He’s going on a car trip with Carol at the end of the week. The first destination is Indiana.

Ed and Carol love to receive letters and messages. If you wish, you can write them: Bejosh Farm, 10 Chestnut Hill Road, Eagle Bridge, 12057.