The following story was sent to me by Sara, a scholar of Russian studies who lives in Washington, D.C, and who has been researching stories about rural and animal life in the Soviet Union in the 1930’s. She has been reading my writing about the New York Carriage Horses and believed a story she found might be relevant. It is. I thank her for it. It is a true story, told by a Russian carter and found in Brooklyn as part of an archive on Russians who emigrated to the United States before World War II following the collectivization of Russian farms and the confiscation of farms and farm animals by Josef Stalin. Crandall provided me with her research, some written in the hand of Arseny Yenotov, a Russian immigrant to the United States, and his children. I wrote this parable from her information and Yenotov’s own accounts. The story does not need elaboration from me, it speaks for itself.

___

Arseny Yenetov was the son of a poor Russian peasant family in the village of Pyrohiv, a small town South of Kiev in what is now the Ukraine, he was born just before the turn of the century, a time of great upheaval for his country..

Life was hard for Yenetov’s family. His father eked out a living on their small farm, and also from their big draft horses, who transported goods for merchants and farmers, carried people who had no horses or carriages of their own, and were rented out to farmers to help them plow their fields and haul lumber. The horses did hard work for long hours, but Yenetov senior was careful to give them rest whenever he could.

The big horses made the difference between starvation and existence.

In harsh times, Arseny’s father would have no choice but to kill one of the horses – he never had more than a half-dozen – to provide food for himself, his wife and his children. Arseny wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps, but there was little work available in Kiev or anywhere else for the son of a peasant farmer, whose family existed on rabbits, cabbage and potatoes and beets – those in good times. He often had stew for breakfast and dinner, very often there was no lunch.

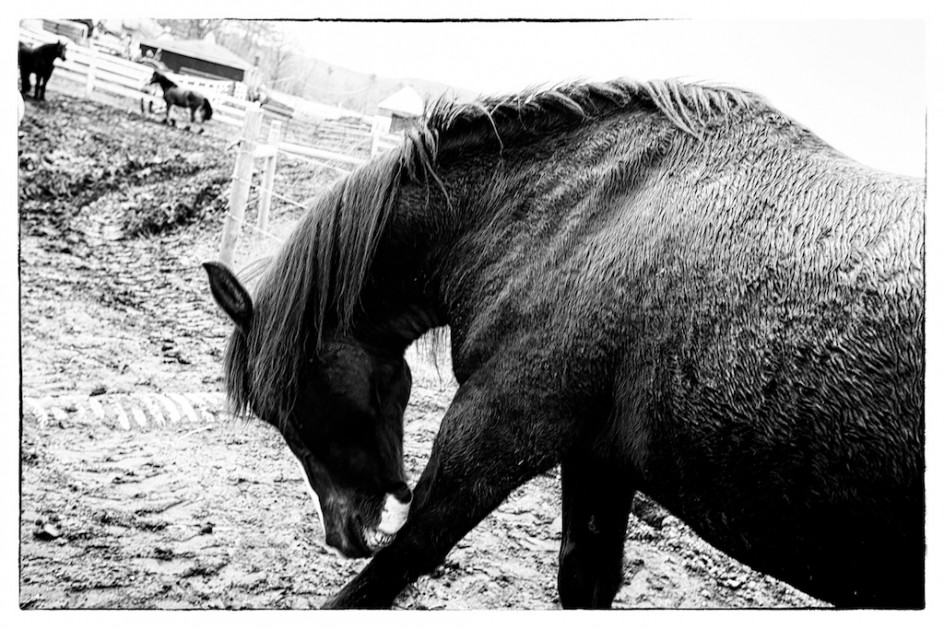

The summers were brutally hot, the winters harsh, there was unimaginable poverty and suffering all around. The horses worked almost every day of the year that the weather would permit. When he was 17, Arseny’s father came to him and gave him a gift of Litany, the boy’s favorite horse. His father told him that their working horses had always kept the family alive, had always provided work, and he hoped Litany would do the same for him. Arseny gratefully accepted ownership of the horse and decided to become a carter.

He and Litany were business partners, he told the horse. They would run their new business together. Arseny had always loved the big black horse, he loved him all the more now.

Arseny built a wagon out of wood that he cut down in the forest. That hand-built carriage was his office and his business. He and Litany began hauling lumber, goods, and crops back and forth to Kiev and other cities in the Ukraine. Arseny and his wife worked hard – she was a seamstress – but they almost always enough for them and their three children. Litany was providing.

It was a terrible time for rural people in Russia. In the late 1928, Josef Stalin had ordered the collectivization of farms, a program that lasted from 1928 to 1940 that was designed to force individual farms into giant collectives. The government and the ideologues and theologists of the Communist Party sought to end private ownership of all farms, crops and animals.

The collectivization movement – an ideological movement spring from within the Communist Party and embraced by Stalin – was fanatic and unyielding in its pursuit of the Russian farmers who owned their land and their animals. There were no exceptions, there was no negotiation, no dialogue, no mercy or compassion, no empathy. It was, as history soon demonstrated, an irrational movement based on theory and party fantasy, not on fact or common sense. “It was a fever,” wrote one historian, “a kind of hysteria.”

Millions of people and animals were to perish of starvation and violence in the great confusion, inefficiency, corruption and famines that followed. The country’s farmers and rural people were ordered to surrender title to their lands and their animals to Communist Party officials. Many resisted, some violently, burning their crops and killing their animals rather than giving up their property and way of life. They were brutally punished, killed or sent to labor camps in the far north.

Arseny struggled to keep his own family alive, but he could not save his parents. His father resisted the collectivization program – he tried to organize the other farmers – and he was taken away in the night and was shot. Arseny’s mother died of a lung infection in the weeks that that followed. The story of the Yetenov family was by no means unusual, it was the story of many millions of Russian farmers.

Day after day, Arseny read and heard the warnings, the threats and pledges that no farmer could own any longer own his own farm or his own horse or cow or donkey. At first, he couldn’t believe it, he didn’t imagine it could be true. One day a local official came to Arseny’s barn and he told him that a complaint had been filed against him by some of the other villagers, they had reported him to the police and the party ideologues. It was said that he had kept a patch of beets and potatoes for himself, and had also kept his horse rather than turn him over to the collective outside of Pyrohiv.

At this time, a second wave of collectivization had been ordered, many farmers were being rounded up and arrested. The official told Arseny that he had to surrender the horse or face arrest. There was no appeal, no negotiation.

Under the ideology of collectivization, farms and property no longer belonged to individual owners, private ownership was now considered a cruel betrayal of the people. Arseny had been denounced in his own village, insulted and shunned. He was suddenly a hated man, ordered to appear before the town’s mayor, who was also a Communist official.

Defiant, he told the mayor that collectivization was unjust. He had committed no crime, he said, broken no laws.

The mayor and the other Communist Part officials – the ideologues of the party – were immovable. They accused him of being a capitalist, a greedy man, a betrayer of the people and an abuser of the system. Arseny protested that he was doing what farmers had been doing for thousands of years, that he loved his horse and had raised him from a foal. No one had the right to tell him what to do with his horse or to take his horse from him or force him to do work he did not want to do, certainly not in the name of the people. Was he not one of the people also?

The ideologues of the Communist Party did not listen, they said Arseny was a greedy criminal, an enemy of the people.

Arseny was escorted out of the meeting, beaten in the streets, escorted home. He knew his troubles had just begun. That afternoon, the secret police came to his home, confiscated his rough wooden cabin and evicted him and his family. They had been give one night to prepare to leave. He was told he would be leaving the house in the morning with his wife and three children and would be taken to work on a farm collective 100 miles from their home. The farm was chosen for them, they had no choice about where to go.

Litany belonged to the people, Arseny was told, where he would do good, be safe, not exploited for personal gain and profit.

Arseny knew that was not the real destination for him or his family. So many of his friends and fellow farmers had vanished into the vast system of Siberian camps known as the Gulag. He had little doubt that was where he and his family would be taken. Litany would go to a collective.

Arseny had heard – and seen – that most of the horses on the collectives died quickly of starvation or overwork or physical abuse, as did many of the workers. The horses were whipped and beaten continuously and worked outside day and night in the brutal elements, in heat and cold, rain and snow. He took his hunting rifle, went to the barn and, sobbing, shot Litany twice through his forehead. Litany, who was devoted to Arseny, trusted him and stood still. He started, trembled, then fell to the ground. Arseny wrote in his diary that the horse trusted him to the end, and that he would never forget that moment as long as he lived. He said no one could ever understand what it meant to lose a good horse that you loved and depended upon.

In the middle of the night, Arseny stole a mule from a farm down the road, attached it to his cart and fled his village with his family, following in the footsteps of Jews (Yenotov was not Jewish), farmers and displaced merchants fleeing the Stalin regime in great numbers. It took the Yenetov family – there were five of them altogether – three months to cross from Ukraine into Western Europe and then to Poland. Along the way, one of their sons died from an infection. The family worked as laborers in Warsaw for five months in order to earn their ship passage to America.

They decided to go to America, Arseny wrote later in his journal, “because there, no one could ever come and take my horse and my property away from me, my children(s) could live in freedom, they would never have to give up a horse they loved or be forced into labor they did not want to do.”

The Yenotov family came to Ellis Island in the mid 1930’s and settled in Brooklyn, then Queens. Arseny realized that horses were the only thing he knew, the only work he had ever had or wanted. He went to the stables in Manhattan in New York City, as a number of other Russian and Irish immigrants had done, and he told the stable owners that he knew horses well, and could brush and shoe them. He began work as a stable boy, cleaning the stables, trimming the horses hooves.

Arseny rebuilt his life. He worked in the stable for several years before he was offered a job as a carriage driver. Then, he became a carriage owner. He was, he often said, a proud representative of the American Dream. And all because of horses, they had saved his life from the beginning and always put food on the table for his family.

Arseny Yenotov loved his job, his work and life in the great city. He was never wealthy, but he always made a good living, there were always people who loved riding the carriages in the park. He was grateful to work for himself, and in the beautiful park. He fed his family, saw his grandchildren. He had a better life than his father even imagined, and it was a life he hoped to pass on to his sons. To the end of his life, Arseny drove his carriage proudly throug Central Park, regaling the tourists and newlyweds with poems and songs from Russia. He blessed America at dinner every single day for offering him such a good life, so much freedom, so different than the awful hardships he suffered in Russia.

He named the first carriage horse he had, and every one after that Litany.

Yenotov died in 1940 from complications from tuberculosis, he is buried in Brooklyn.

__

After reading his story, I wondered what to make of the effort by animal rights organizations and the city government to banish the horses and carriage work from New York. I suppose it is a good thing Arseny did not live to see it some of his own painful history repeating itself. Here, in New York City in 2014, government officials and powerful ideologues are knocking on the door of the stables to tell the carriage horse owners and drivers that they can no longer keep their jobs, that other work has been chosen for them, and to denounce them in public hearings and protests as greedy and selfish and uncaring. They have vowed almost daily to take their horses – their animals and the source of the food on their tables – away from them and to force them to give them to other people who will never allow them to work again.

America in 2014 is not Stalin’s Russia in the 1930’s. Yet there are echoes of Arseny Lenotov’s story all around the story unfolding in New York. It is is perhaps not as different as it ought to be. I think of Tony Salerno who helped save his horse and the people around him from injury last Thursday and who finds himself the target of powerful bureaucrats and ideologues in and out of government seeking to take his work and horse away without cause. He has committed no crime either, and broken no law. I think of one of the carriage drivers I was talking to in Central Park and what he told me, his eyes blazing. “Who are these people anyway, that they think they can come and invade our lives like this, tell us who we are and try and take our work and our horses from us? If that happens, it will be a sad day for us, but it will also be a sad day for everybody else. Is this the same country my grandfather came to from Ireland?”

__

it is possible that one of Arseny’s descendants is driving a carriage still. If so, I will find him or her. If you are interested, you call learn more about Stalin’s collectivization program here.